Why I'm Testing Tailwind for My First 50K Nutrition Plan

Are you familiar with the mixture of horror and dread that builds when your stomach churns after smashing an experimental gel while you’re miles from the nearest toilet?

Your mind immediately shifts into damage control mode, forming contingency plans to start limiting the inevitable ego-damage and humiliation. Every bush becomes a potential emergency shelter. Meanwhile, your legs keep moving because, well, what choice do you have?

Pro tip: toilet paper belongs in your trail running kit. Trust me on this one.

There are few things that make me seriously question my endurance sport pursuits. Subjecting my digestive system to the chaos of breaking down food while I’m running in the heat-stroke-inducing heat and humidity of a Southern Illinois summer? That’s definitely one of them.

Picture this: dew points in the high 70s, humidity in the 90s, and heat indices in reaching triple digits before most people finish their morning coffee. Training for a 50K in these conditions makes thoughtful hydration and nutrition mandatory.

Here’s what I’ve learned after months of trial and (literal) error: mixing nutrition with hydration gets the job done. Sure, I've thrown a few gels and chews into the mix during long runs, but I keep gravitating back to their hydration blend.

The math has been challenging this summer. I can drop 3-5 pounds in water weight on a single long run, even while consuming 20 ounces of hydration mix every hour. In conditions like these, liquid calories aren't just convenient, they're essential. I need fluids. I need electrolytes. Long runs demand carbohydrates for fuel.

It's a perfect storm of necessity, and a hydration mix checks every box.

The Problem with Traditional 50K Nutrition Advice

Most nutrition guidance offers the same tired advice: “consume 200-250 calories per hours” and “try different foods and see what works.” It tops it off with the exceptionally helpful guidance to “practice during training.”

Here’s the thing: none of this advice is wrong. It’s all technically correct. You absolutely need to consume a few hundred calories per hour and dial in your strategy during training. But this generic wisdom is maddeningly useless when you're staring down your first 50K in a few months.

It's like telling someone to "just be a good driver" without explaining how to parallel park. The advice covers the what without addressing the how, when, or what happens if it all goes sideways.

The First-Timer's Paradox

You need experience to know what works, but you can't get that experience without risking everything on race day. It's a nutritional catch-22 that generic advice completely ignores.

Consider the timeline reality: Even if you started planning your nutrition strategy months ago, you're looking at maybe 6-12 solid long runs to test everything. That's not nearly enough runway to experiment with multiple strategies, fail safely, and still have time to nail down what actually works.

And here's what those guides won't tell you: What keeps you fueled during a comfortable 18-mile training run might revolt spectacularly at hour 5 of your first 50K, when fatigue, stress, and adrenaline have turned your digestive system into a war zone.

The Stakes Are Higher Than You Think

Scan any ultra DNF list and you'll see the usual suspects: injury, inadequate training, poor pacing. But dig deeper and you'll find the silent killers—GI distress, dehydration, and bonking. The nutritional failures that turn months of training into a death march can be traced back to the starting line.

Training your gut is as crucial as logging miles or preventing injury through strength work. Yet a lot of us treat nutrition as an afterthought, something to figure out "eventually."

That's exactly the trap I was headed toward until I realized I needed a completely different approach.

Why Tailwind? The Engineer's Decision Matrix

I’m currently training for the Hennepin 50K, which is about five weeks out. I have a few more long-runs to further hone my nutrition strategy. I want to focus in on what has already been working. As a race gets closer, I like to remove variables instead of introducing new ones.

The race doesn’t use Tailwind at aid stations, which means that I’ll have to pre-mix and carry my own during the race. I generally opt to pack my own rather than rely on aid station hydration mixes, as you never know how it’s going to hit your digestive tract during the race. I’ve also already been training - running and cycling - with Tailwind through the heat of the summer. I can tolerate high concentrations in high heat. I’d rather stick with it what’s familiar rather than switch to the race’s hydration/nutrition sponsors.

Those with iron stomachs may feel differently, but I attempt to avoid GI distress at all costs.

Decision Criteria Framework

What does this mean in practice? Here’s what I’m looking for my first 50K nutrition strategy testing:

Alternatives Considered and Rejected

- Gel + Sports Drink Strategy: at this point, there are too many variables. I haven’t found the “perfect” gel yet. Introducing a gel now feels like playing with fire, and I’d rather not blow up my race.

- Real Food Approach: Real food might be great for 100-milers, but it’s overkill for 50K. I’m hoping to finish the race in fewer than 6 hours, and I plan to save the solids for post-race celebrations.

- Multiple Product Strategy: I’ve thought about switching to the hydration/nutrition product that Hennepin 50K is providing at aid stations, Fuel2o. But, I’ve never tried the product, and getting started with it now isn’t prudent.

Tailwind's Tech Specs

From Triathlon to Ultra Running: My JourneyI’m currently embarking on a self-guided, graduate-level study of sports nutrition and physiology. This project is still early days, but I have received all of my text books in the mail and am digging into several books. It’s a fun application of my undergrad bio & chemistry.

Absorption Game

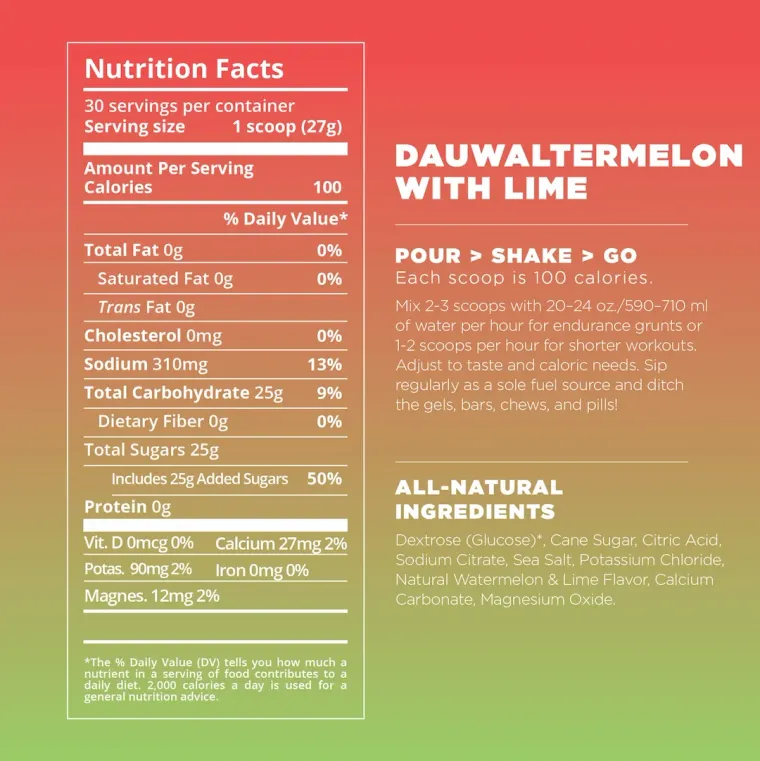

Carbohydrates per hour is the current name of the game. Most people think sports nutrition is just about getting calories in, but absorption is where the real magic happens. Your body has specific pathways for absorbing different types of sugar, and glucose and sucrose use separate transport mechanisms. When you combining them, you can theoretically absorb more total carbohydrates per hour than with either type of sugar alone.

There’s research and anecdotal race reports suggesting that mixed-carbohydrate solutions can increase absorption rates from about 60 grams per hour (single carb source) to 90+ grams per hour. For a 50K that could last 6+ hours, that difference in fuel availability could be the margin that keeps you running rather than crawling over the finish line.

But here's the kicker: this only works if your gut can actually handle what you're ingesting.

Why Your Stomach Rebels

Ever wonder why that gel that tastes fine at mile 6 creates misery by mile 20? Yes, it could have something to do with the 14 miles between both points in time. But it also has something to do with the molecular complexity of what you're asking your digestive system to process while traversing those 14 miles.

During exercise, blood flow gets redirected away from your digestive organs and toward your working muscles. Your gut essentially goes into power-saving mode to support the demands of exercise. Complex molecules, thick textures, and high concentrations of sugar can sit in your stomach like a brick, fermenting and causing that familiar churning sensation. (aka gas, bloating, cramping, and/or explosive diarrhea).

Liquid nutrition can help avoid some of these problems, especially compared to solid foods. Liquids moves through your digestion system faster and requires less work to process. That makes intake more efficient and less painful.

The key is finding the right concentration. If it’s too strong, you’ll end up with GI distress. If it’s too weak, you might start to feel run-down later in the race.

The Protein Debate (Spoiler: You Probably Don't Need It)

Depending on your sport background, you may be surprised to learn that you don’t need to include protein in your first 50K nutrition race-strategy. Running longer distance doesn’t automatically mean that you need protein during the race.

Multiple studies comparing carb-only drinks to carb-plus-protein combinations show no meaningful difference in endurance performance for events lasting under 3-4 hours. For most first-time 50K runners (finishing between 5-7 hours), the evidence gets murkier, but the potential downsides become clearer.

Protein is metabolically expensive to process. During exercise, when your digestive system is already compromised, adding complex molecules to the mix increases your risk of GI distress without providing clear performance benefits. It's essentially adding variables to an already complex equation.

This doesn't mean protein is bad. It’s critical for recovery - I include protein in all of my post-long-run nutrition.

But during the race? The risk-reward calculation doesn't add up, especially for someone testing their first 50K nutrition strategies on a limited timeline.

The All-In Bet: Just Tailwind and Water for 31 Miles

Here's the experiment: fueling my entire first 50K with nothing but Tailwind and water.

No gels. No chews. No backup snacks or tasty aid-station treat. Just liquid nutrition from start to finish.

Depending on your perspective, it’s spectacularly simple or naive. Elite and experienced ultrarunners pull off these sorts of feats regularly, but they also have guts of steel and years of trial-and-error refinement. Can the same approach work for your average active-30s endurance enthusiast?

Why This Might Work

I'm not going in completely blind. I've been training with Tailwind all summer, running and cycling. My digestive system knows what to expect. More importantly, I've successfully experimented with increasing the concentration to pack more calories into each sip without triggering radical GI upset.

The math looks promising too. At my tested concentration, I can consume 300-400 calories per hour while staying mostly hydrated (depends on the dew point, I’m a sweat machine).

For a 6-hour 50K, that puts me right in the recommended fueling range without the complexity of juggling multiple nutrition sources.

Single-source nutrition also eliminates variables. If something goes wrong, I know exactly what caused it. If everything goes right, I know exactly what to replicate for future races.

The Glaring Weakness in My Plan

But here's where my summer of testing might actually work against me: I've been training in absolutely brutal conditions. We're talking dew points in the high 70s, humidity pushing 90%, and heat indices regularly hitting triple digits.

In that furnace, consuming 20+ ounces of liquid per hour wasn't just comfortable, it was completely necessary.

The Hennepin 50K happens on a cool October night. Without the sun beating down and temperatures potentially dropping into the 50s (or 40s!), I might need half the fluid I've been training with.

Potential disaster scenario: What if I can only stomach 10-12 ounces of liquid per hour in cooler conditions? At my current concentration, that cuts my calorie intake nearly in half. Instead of 300-400 calories per hour, I'm looking at 150-200 calories. That’s likely adequate to finish strong, but far less aggressive.

I'm essentially betting my first 50K on the assumption that I can force down liquid calories even when I’m not dripping in sweat. It's either going to be elegantly simple or a masterclass in poor race execution.

Only one way to find out!

My 4-Week Testing Protocol

Over the next 4 weeks, I'm committing to this Tailwind-only strategy publicly because it forces honest reporting and holds me accountable. If this approach fails at Hennepin, you'll get the full post-mortem.

This week, I'm testing how the strategy performs in cooler conditions during a 16-mile run. I'll share those results Wednesday, followed by data from this weekend's long run next Monday.

Here's exactly what I'm tracking in my n=1 research study:

Quantitative Metrics:

- Exact calorie intake per hour

- Fluid volume consumed

- Pace maintenance/degradation

- Heart rate correlation

- GI distress scale (1-10)

Qualitative Tracking:

- Energy level perception

- Flavor satisfaction/fatigue

- Stomach fullness/comfort

- Post-run recovery quality

The real experiment starts now! I'm either going to validate a elegantly simple fueling strategy, or learn exactly how not to fuel a 50K.